A Brief History of The King’s School, Canterbury

The King’s School, Canterbury is often described as the oldest school in England. Such a claim is impossible to verify, but there is at least some justification in associating the School with the origins of Christian education in England. A school was probably established shortly after St. Augustine’s arrival at Canterbury in 597, and it is from this institution that the modern King’s School ultimately grew. In 1997, the School therefore participated fully in the celebrations of the 1400th anniversary of the coming of St. Augustine.

Very little is known about the Canterbury school in the early centuries of its existence. During the Middle Ages, however, there was clearly a school attached to the Cathedral and run as part of the monastic establishment. There are definite references to Headmasters from the later thirteenth century, but little other evidence of this school’s existence survives. Despite the obscurity of these early years, the King’s School nonetheless feels that it is rightly associated with its predecessor and there are stained glass windows commemorating former pupils St John of Beverley and St Aldhelm in the School’s Memorial Chapel.

The fully documented history of the School really starts in the sixteenth century. With the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the School was re-founded by a Royal Charter in 1541. This established a Headmaster, a Lower Master, and fifty King’s Scholars. The name ‘King’s School’, now used for the first time, thus refers to King Henry VIII. Soon afterwards, through the beneficence of Cardinal Pole, the School moved to the Mint Yard and acquired the Almonry building, on the site of the present Mitchinson’s House, which was used for some 300 years.

The revived School quickly established its reputation, not least thanks to its first Headmaster, John Twyne (c1524-62), and in the next hundred years a number of former pupils (now known as OKS or Old King’s Scholars) achieved national fame. Among these were Christopher Marlowe, the playwright contemporary of Shakespeare and author of Dr. Faustus, William Harvey, the scientist who discovered the circulation of the blood, and John Tradescant, the distinguished gardener and collector.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the School survived the disruption of the Civil War and some less than distinguished Headmasters. It remained a successful grammar school, educating boys largely from Canterbury and Kent. Under one remarkable Headmaster, Osmund Beauvoir (1750-82), it achieved wider fame. His pupils included Charles Abbott, later Lord Chief Justice, and Sir Samuel Egerton Brydges, the eccentric man of letters.

It was the Victorian Headmasters George Wallace (1832-59) and especially John Mitchinson (1859-73) who transformed the King’s School into a ‘public school’ with a national reputation. The buildings were improved, most notably with the new Schoolroom of 1853, and academic standards raised. Mitchinson’s period in office unfortunately ended in a rebellion by the boys, and he left to become Bishop of Barbados. One other aspect of this Victorian development was the growth of organised sport, with cricket and rugby football the most important. Cricket had been played on a casual basis for some time, and some games were even played on the Green Court as shown in this 1865 photograph. In addition, the boys were now able to use the ground of the famous Beverley Club, now the St. Lawrence Ground, which is still the headquarters of the Kent Cricket Club today.

Despite this growing emphasis on games, the School’s most distinguished old boys were literary figures. Walter Pater, the influential critic, and Hugh Walpole, the popular novelist, are well known. Even more famous is Somerset Maugham, who wrote about his schooldays in Of Human Bondage, where the School is thinly disguised as ‘The King’s School, Tercanbury’. In the twentieth century this artistic tradition has been continued with the notable film directors Carol Reed, Michael Powell (who returned to his home county to make A Canterbury Tale) and Charles Frend.

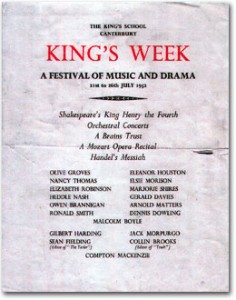

The modern development of the School was largely the achievement of Canon John (‘Fred’) Shirley, who became Headmaster in 1935 when the School was suffering from the effects of the Depression. Through his dynamism and financial skill, he saw the School expand rapidly in numbers from under 200 to over 600 pupils in nearly 30 years. He also acquired and built several more buildings in the Precincts. In his time, too, the School survived the war-time evacuation to Cornwall and received a new Royal Charter from King George VI and Queen Elizabeth in 1946. Above all, the School grew in reputation, thanks to its academic, sporting and cultural success. ‘King’s Week’, the festival of music and drama at the end of the summer term, was started in 1952.

It is no surprise that modern OKS have achieved fame in a variety of fields, including literature (Patrick Leigh Fermor, Edward Lucie-Smith and Michael Morpurgo); music (Louis Halsey, Harry Christophers and Christopher Seaman); politics (Lord Garel-Jones and the Powell brothers, Charles and Jonathan); and sport (David Gower and Frances Houghton), as well as in business, journalism, science, education – in this country and around the world.