It is now rather more than 40 years ago since I first entered the King’s School, and when I look back at school as it then was, and compare it with the School of the present day, it is hard indeed to recognize my old friend, for with the exception of the name and the number of the King’s Scholars everything is changed; even the very buildings are all gone, and there is no trace by which a King’s Scholar of forty years ago can be reminded of the School of his early days.

Let me try and picture to you somewhat of the old buildings. The School proper stood at the South end of the Mint Yard and extended from Northgate, where Hayward’s lodge now stands nearly up to the Green Court Gate, which was at that time the entrance to the Precincts, the old gates now hanging at the gate in Northgate, then being hung on the hooks still existing at the Green Court Gate, the Porter dwelling where the present carpenter’s shop is, his sleeping apartments being overhead. You must remember that the present Schoolroom was not erected till 1851, the two arches extending from the Norman Staircase to the carpenter’s shop being all that was then left of the ruins of the old “Hog Hall,” the open space under the present School being known by the name of “The little Mint Yard;” at one corner, of which dwelt a lady of great celebrity, and one much respected by all boys who knew her, this was celebrated Mrs. Norton, purveyor of luxuries and dainties, in the shape of tarts, buns, &c., to the King’s School; the said lady dividing her attentions between the providing of delicacies and the careful culture of a pig or pigs in close proximity to her dwelling house, which pigs if they did not conduce to the sweetness or salubrity of the neighbourhood, yet in due time produced great delight to the boys of old, when they appeared in the shape of sausages, &c., and helped to swell the exchequer of the said lady.

Where the present Library stands was the old Choristers School, approached by the Norman staircase, but this School was afterwards removed to one of the rooms then existing over the Dark Entry. The site of the present Headmaster’s residence and the Dining Hall was occupied by three dwelling houses, let to outsiders. The Gymnasium has taken the place of the second Master’s House. The Classrooms, north of the Colossal staircase, stand on the site of the Organist’s official residence, and the Headmaster’s house as part of the School building, next to Northgate, Hayward’s lodge being about under the drawing-room. The Grange was at that time occupied by outsiders, and where the present Headmaster’s garden is, was then the yard used by the Cathedral workmen. So really all the School building, strictly speaking, consisted of the Head and Second Master’s House, and the big Schoolroom, which I will describe presently; the long room, where the Boarders had their meals and did their evening work; and bedrooms, yes bedrooms, not dormitories, and such rooms as I fear the present generation would rather elevate their noses at, for in some of them there was almost more bed than room.

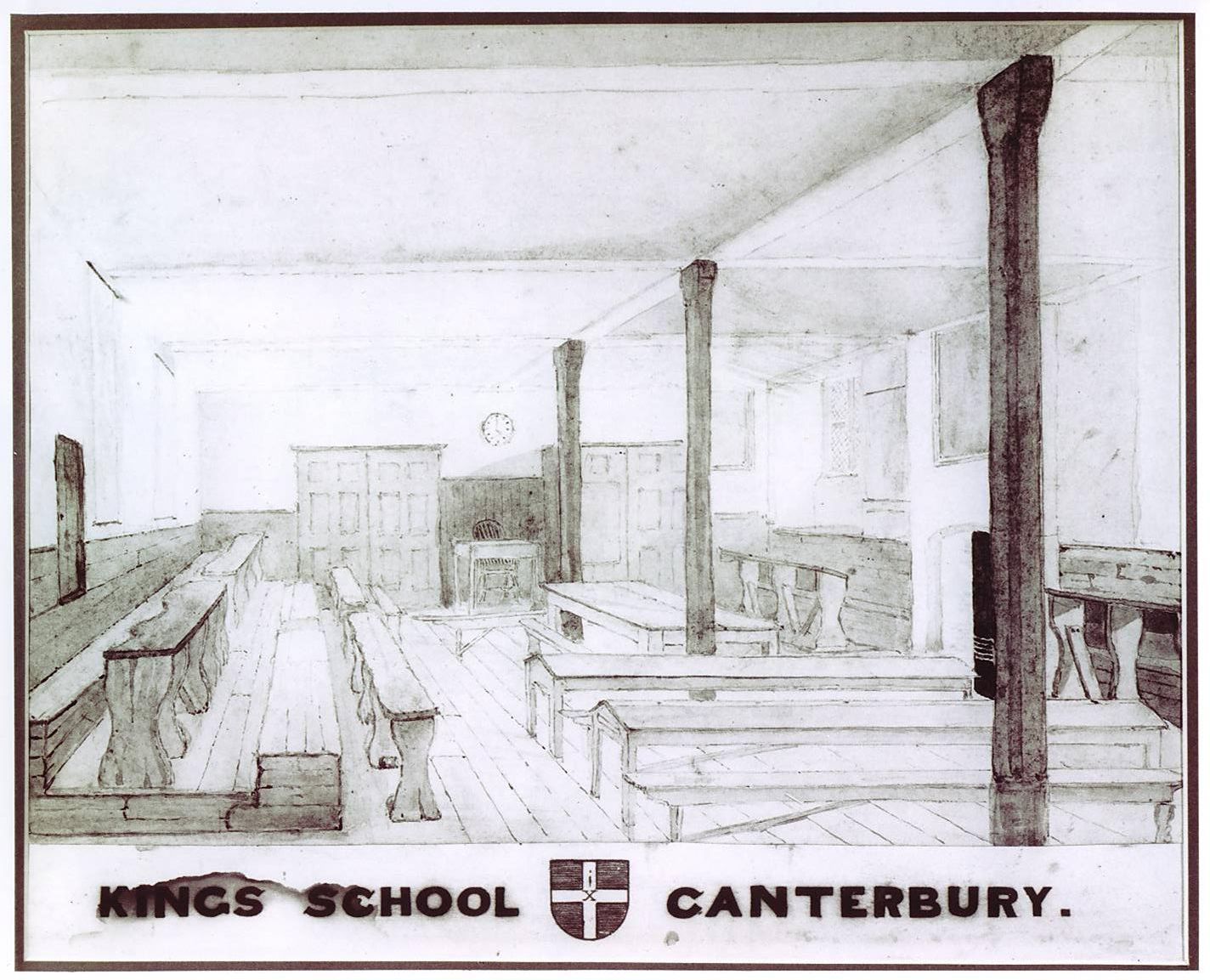

There the big Schoolroom with its appointments would hardly have satisfied the requirements of a Government Inspector, had there been such a person in the days I am writing of. Try to imagine a room, as far as I can now judge – about 50 or 60 feet long by 16 wide and about 10 high – with three equidistant wooden pillars or posts of the roughest description down the centre of the room, painted as was also the dado, if I may so call the boarding half way up the wall, a sombre black relieved only by the white-washed walls and ceiling above, – you may guess it was not a very cheerful looking place – the walls were some four feet thick. The windows, which were large, being placed so high that passing objects should not unduly interfere with the severe work of study. There was never much glass in these windows which perhaps was lucky when we consider the use made of the window seats – if again I may call that a seat which was at least five feet from the ground. These window seats, besides being the receptacles for caps and hats during school time, had also a row of small cupboards in each, where the boarders kept their books, &c. I say “&c.” advisedly for well would it have been if books had been the only occupants – but alas! no. Small cupboards with backs becoming rotten by age and decay were worthy of better things, for their backs being removed, a splendid field for engineering presented itself among the flints, bricks, and mortar behind, and many were the neat little caverns picked out in the wall, which caverns as soon as finished to the possessors liking, were tenanted by rabbits, guinea pigs, white mice, or snakes. Fancy that, ye valetudinarians of the present age. Imagine the scent on opening the cupboard door, think of the ammoniacal odours which pervaded the room itself. Were the olfactory nerves of schoolmasters of former days less acute than those of their successors, or how was it that these Zoological repositories were not found out, surely it must have been the friendly gales of fresh air which were continually pouring through the broken windows? However, the zoological tendencies of the King’s scholars were only destroyed by the at length abolition of the cupboards themselves, and however much all may have grieved at the time, I fancy there is not one of those keepers of wild beasts now living who will not agree that it was “a good job too.”

The other arrangements of the room were more formal and perhaps less interesting. Three small tables with armed Windsor chairs for the Head, Second, and English Masters, – fixed seats on a raised platform all round the room for the VI. V. IV. III. forms, the II. and I. having to sit on the edge of the platform in front of the desks of these upper gentlemen – offering grand opportunities for kicking, which I can well remember were by no means thrown away or neglected.

The desks were indeed curiosities. Most curiously cut and carved with the initials if not the full names of former and the then present generation, they were bored and tunnelled most ingeniously, and not without great perseverance, for hard indeed was that old oak of which they had been made, perhaps centuries before my time; many and many were the knife blades which were sacrificed in the pursuit of wished for immortality, before the desired initials were complete in their carving. But alas! for founders’ intentions not only all the carvers no more, but desks, school room, and all have been swept away from the ken of man.

The library which formed the nucleus for the present excellent collection of books, was, in my time, almost entirely supported by funds arising from the fines exacted for being late for school, or for leaving books about, for being late for prayers one halfpenny, and for every additional three minutes an extra farthing, and a halfpenny for each book found lying about. Often and often was there to be seen a goodly congregation of smaller boys at the bottom of the staircase kept there by the threats of the sub-monitor for the week in order to swell his account of fines on the Saturday – there being a friendly rivalry amongst these dignitaries as to who could get the largest sum in his week, the larger the sum the greater the delight of the finer, and the greater the disgust of the fined, notwithstanding the fact that the school library was to be improved thereby.

Then again every knife, top, or other luxury confiscated and locked up in “the Press” for absorbing too much of its owner’s attention during lesson time, cost the unhappy owner one penny before he could repossess himself of his lost treasure. All these fines went, as I said before, to support the school library. It was of course on a very modest scale. A cupboard about 8ft. long by 6ft. wide. just room for the librarian to turn round and box the ears of two eager inquirers after “Felix on the Bat,” Hone’s “Every Day Book,” “Ivanhoe,” “Rob Roy” or Scrope’s “Salmon Fishing,” all vast favourites in days gone by. The books were let out for a week to be returned a few minutes before second school on the day appointed for each form, but should the possessor of a book forget the day or time he was fined one penny per day till it was returned. We had no “Terms” in my time we had “quarters”, we had holidays four times in the year – six weeks at Christmas and Midsummer, ten days at Easter and Michaelmas.

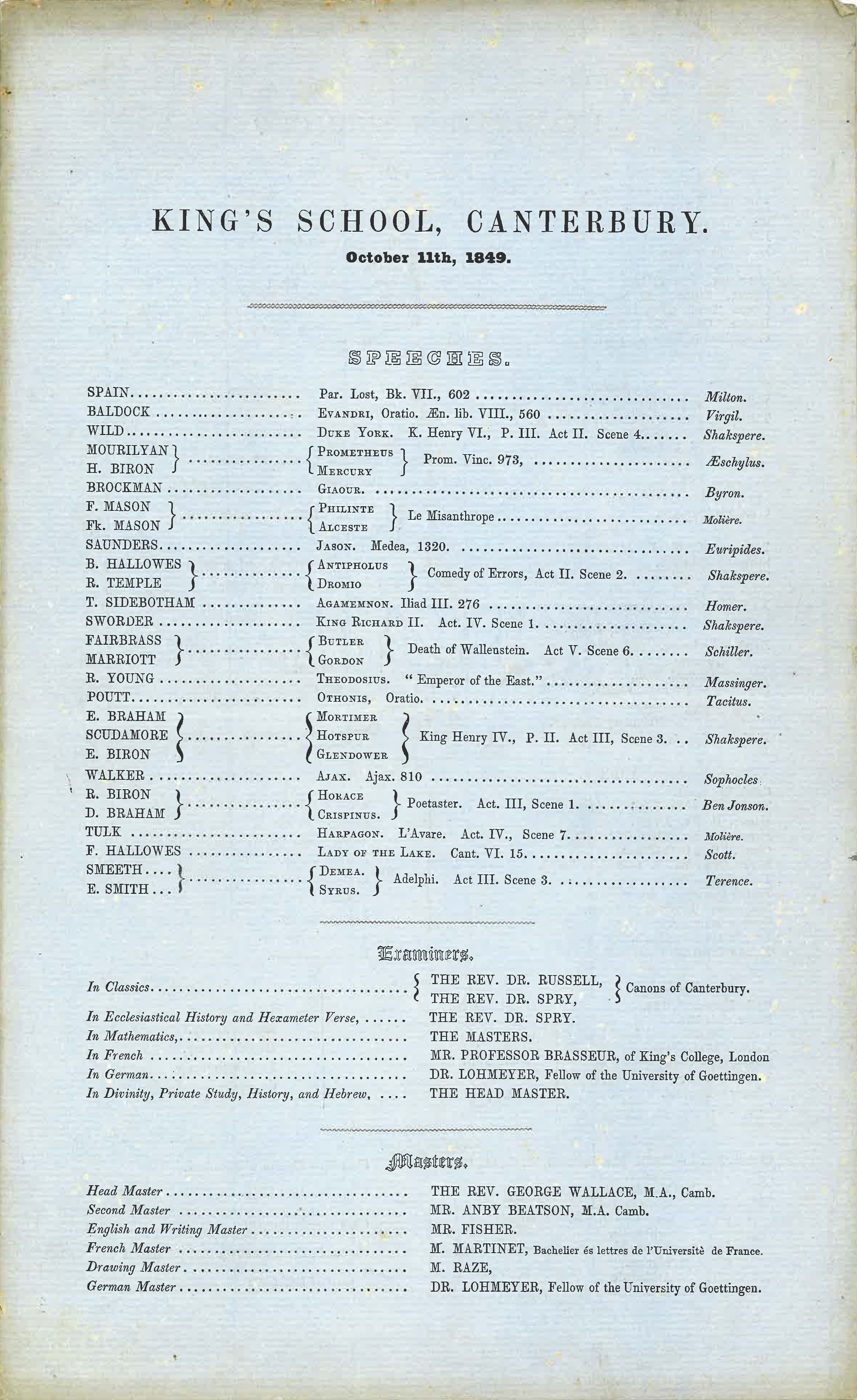

The Speeches always took place just before the Michaelmas holidays, when boys left to go to the Universities in October, and what a glorious vision of ideas and fuss does the very word “Speeches” always call up before me. In those days we took about three weeks to prepare our speeches, during which time the speakers were entirely exempt from all school lessons. Several days were spent in choosing a speech, and getting together the “dramatis personae” and not only getting them together, but in trying to get each one to be tolerably content with the part assigned to him. That was sometimes rather difficult, especially when each one in his heart of hearts, wished to be Hamlet, or Macbeth, or the funniest man in the comedy. Somehow no one ever seemed anxious to take the subordinate parts, but after a time these preliminaries were arranged, and then the Speech had to be copied out, and each speaker walked about with a roll of paper in his hand, a sort of general’s baton to proclaim his dignity of speaking. The said roll of paper being composed of many sheets, soon became a weapon of offence or defence, and I fear a nuisance to all.

Well the speech of course had to be learned, and what pains our dear old English Master, Mr. Fisher, (beloved by every boy) used to take with us, with what a stentorian voice would he shout at us, because we did not enter into and recite our Shakespeare as he would have us to do. How would he show us again and again, and at last come to the conclusion that it were as profitable to “play jigs to milestones” as to try and implant real dramatic feeling into our obtuse understandings – though I fear they appeared sometimes more obtuse than they really were in order to “get a rise out of Old Fisher.”

The Headmaster always prepared the Greek and Latin Speeches which were of a rather more serious nature, and not quite so amusing as somehow he used to get more rises out of us than we did out of him. The French and German were prepared by the native masters of each language, and as discipline is not generally the forte of either French or German instructors, the French and German orators had rather a lively time of it. But the speeches were on the day well rendered and prompting very little needed if at all, though there always was an official prompter provided with fair copies of the speeches written out by the best writers in the lower school, the speakers themselves being far too dignified to write out their own.

Well at last came the speech day. Breakfast was provided for all the speakers by the Head Master, pigeon pies, ham, chicken, tongue, eggs, hot buttered rolls, unlimited tea and coffee. Ah, this was a breakfast looked forward to by boys whose usual déjeuner consisted of stale bread an inch thick with a scraping of salt butter on it, and a basin! I hardly dare write the word in these aesthetic days, a blue basin of very weak tea, sweetened with brown sugar, and very blue milk. How well I remember the peculiar hue of that nasty infusion, but this was all there was for the captain or the lowest boy in the school. Think of this, oh luxurious youth of the present day, while you are consulted as to whether your peculiar liking tends to tea or to coffee, and while you are tickling your palate with some choice tit-bit, think of your fathers’ school breakfasts and will you then wonder when I say that our speech day breakfast was looked forward to with eager longing and even still lingers pleasantly in our memories?

Breakfast over we went to the Cathedral at 11, where the sermon was always preached by an old King’s Scholar, I say always because of late years the practice has (I think unwisely) been departed from, for with what respect and reverential awe did we behold that black gowned, behooded, bebanded, white chokered old school fellow. Happy indeed the VI form boy who could boast of that preacher having been at school with him, although he was then but an urchin almost unknown to the object of his veneration, ah, thrice happy if he obtained a nod of recognition or a shake of the hand from the preacher, for 40 years ago travelling was rather more difficult than in these fly about days. When a boy left school he was very often not seen again till he came to preach on Speech Day, and he was utterly unknown to nearly all the boys in the school, but yet we all looked on that old school-fellow as we claimed him to be as a far greater man and we loved to look on him far more than on any famous preacher of the day, or even a Bishop himself (though Bishops in those days did not preach about much out of their own dioceses), for was he not one of us? Perhaps there was another reason for our liking our preacher and that was that he always preached a short sermon. He had himself gone through the anxious nervous feeling generally attending the début of a public orator, and he could sympathise with those who were so soon to appear on that green baize platform to find themselves confronted by the great world or its representatives.

After service a biscuit and glass of wine was with difficulty swallowed. It is odd how very dry biscuits always appear just before going through an ordeal, but the wine was a great assistance, and helped to supply some of the necessary amount of pluck required by the novice on his first appearance in public. The speeches themselves and the after speeches I need not describe as they were much as they now are, save that there was no admission of the King’s Scholars. This was always done in the School Room immediately after the examination just before Christmas.

I should also like to mention another omission and that was of the, to my mind, unseemly cheering and shouting in the Cloisters, after the speeches. Surely God’s Acre is consecrated, and such noises are hardly in accordance with the resting place of the dead, and would hardly be allowed in a cemetery of any kind, whether consecrated or not. I for one should rejoice to hear that those maniac shouts were reserved for some other place, but verbum sap.

As regards our school work in years gone by there was not much difference I expect from that of the present day. Only that the division of the day was different, after Easter to Michaelmas, we began school at 7. This lasted till 8.30, we began again at 9.30 and went on till 12.30 and again from 2 till 4. Half holidays on Wednesdays and Saturdays, when we got leave to go out at 2.30 and were free till the tea bell rang at 6.

We attended the Cathedral service every Friday morning, instead of Saturday afternoon though Saturday had been the day previously to my time. On every Friday morning before Church the Church catechism was said by the whole school, the captain, in the presence of the Head Master interrogating the Upper School, while the Second Master performed the same office for the Lower School. We attended the Cathedral services on all Holy days, the rest of the School day being devoted to the study of the Greek Texts.

The examinations were held at the end of the Midsummer and Christmas quarters, by two of the Canons, Drs. Russell and Spry, that for the King’s Scholarships being held during the November audit by Dr. Russell and the Vice Dean, who was then in office for a year at a time. The Scholarships in those days were worth but £1 8s. 4d., and the classical education free and it conferred the privilege of being eligible for a school exhibition at the Universities. No boy in my time could try for the King’s Scholarship until he had been in the school for twelve months. There was one curious custom connected with the examinations the origin of which I never knew and that was the hanging by the neck a small paper demon over the entrance to the Great Schoolroom. I do not remember ever seeing anyone place it there, but there it always was. Perhaps some other “antiquity” of the King’s School will be able to enlighten us when he reads this reminiscence of school days.

I will now say a few words about the games of the old boys. Of course then as now cricket was the most honoured of all our games. Our only cricket ground for the first half of my school life was the Green Court, during the latter half we as a club subscribed to the Beverly and used to play all our matches there, but at first the Green Court witnessed all our triumphs and defeats, and what labour did we bestow on the pitch during April ready for the 1st Monday in May which weather and headmaster permitting was always our opening day. We rolled, we watered, we tendered it with loving care There was no Goodhew then, with mowing machine and men to work it – no, the simple scythe of the husband of our pie-woman did all the mowing and we did all the rest, the horse roller belonging to the Dean and Chapter, drawn by a dozen willing or unwilling pairs of hand, with a few big boys seated on top, either for the sake of increasing the weight of the roller, which the team of draggers never saw the need of, or else for the sake of carriage exercise, was the only machinery we had, but our pitch was always a good one, at any rate, for the first day, and if, afterwards, it got a bit bumpy, well, we enjoyed the pleasure quite as much, and, although we had no instructor or professional, we turned out some good cricketers.

There was a most wholesome system of cricket fagging, each form in the Lower School providing in turn fags for the practice of the Upper School, and woe betide that boy who shewed fear of the ball, he might let it pass through his fingers, but as surely as he did so, so surely was he summoned to the batsman, who gave him a good dose of either bat or wicket sauce, and we knew how highly that sauce was seasoned by the stinging sensation that fondly lingered over our hands for some time after. Nearly every afternoon in the summer quarter there was some match arranged. Not merely practice before a net, in fact a net was never seen in those days, but a properly played match which afforded good practice at fielding as well as batting, and insured a pretty good eleven when wanted, and an eleven pretty good all-round.

In October we began football; what is now called Association, was our game, we never heard of Rugby. This we played also on the Green Court, the lower goal was on the west wall of the Green Court (the remains of the L.G. was still visible a year or two ago, and I daresay is so still.) The upper goal was marked U.G. on the wall in front of the Deanery which stood outside the lime trees, and in fact was the continuation of the east wall of the dark entry. The entrance gates to the Deanery then stood close by the Dark Entry. Another game which seems to have quite died out, was the good old English game of hockey. This for the most part filled up the time between the decease of football and the renewing of cricket, our ground for this, notwithstanding the constant interruptions by carts and carriages was the roadway on the west side of the Green Court, our two goals being the Larder gate and the gate of the Archdeacon’s stable yard, which occupied the now vacant piece of ground at the end of Mr. Gray’s house. His house and that of the Precentor being then all one house and the residence of the Archdeacon.

Well, there were many minor games, but I almost fear to mention them, lest I should shock the minds of the present generations, but I hope their shuddering won’t be too severe when they learn that former generations of King’s Scholars actually played at marbles, and this always in dirty, wet, wintry weather, and I fear with some that the dirtier the weather the greater was the enjoyment, and we did not even disdain to play at peg top, islands hopscotch; the latter two games are now obsolete, requiring certain mysterious bases, marked out by the heel of the boot or shoe and a piece of tile. Many a precious bit of lucky tile found a safe resting place in the pocket of its proud possessor; Then there were “black sheep,” “prisoner’s base,” “fly the garter” and others too numerous for description. Of course when the elements afforded material, sliding, the slides somehow always being the best when made on a pathway or in some dangerous situation.

Snowballing of course was a regular thing in the old winters of by gone days, and many were the pitched battles fought with the “street cads” in the roadway between Northgate and the Prior’s gateway carried on with hearty vigour till the well-known form of the Headmaster’s bald head was seen appearing at his dining room window, then our arms were laid aside with astonishing celerity and off we had to skedaddle as our American cousins say, for though by no means afraid of our snowballing foes, yet we were in awe of the impositions and punishments: which were sure to come on those who were recognised by him whose word was law.

Perhaps it would be more to the tastes of the present day if our fightings had been confined to snowballing, but this was not the case; fighting with one another, though of course “strictly forbidden” was by no means an unusual occurrence in the days I am writing of. I may go further and say that not many a morning passed without a pugilistic encounter of some sort. Immediately after morning prayers at 8.30 was the time and the arena was at the back of the Norman Stair Case. The cause of quarrel may have been small, but the battle was grand, and marvellous were the imaginary accidents to which the black eyes were attributed. Any one would have imagined that bed posts were always presenting themselves on purpose to be run against, or else that the knees of the boys were very weak, so numerous were the tumbles, but some how the eyes and nose were the only members that suffered. Well to make a long story short, by fair open fighting boys learned their own value, they found their own level in the school and learned not to be cowards, surely this, whatever mammas of the present day may think was better amusement than roasting little boys in front of the fire, till their clothes and even their flesh was scorched if not burnt. Fighting boys made none the worse men and in after life showed no less Christian spirit but a great deal more, than sneaking bullies, who dared not fight, but had no objection to torture the small and weak.

Paper chases were much in vogue in days gone by, though restriction was wisely placed on the course not being laid through the river, one poor boy in my time having died through a chill caused by swimming through the river after running. Our bathing place was at Bingley close by the present Swimming Baths, which of course were not then existing. One boy taught another to swim and proud indeed was the small pupil when he first accomplished a safe journey through the perils of Bingley Hole.

As to mischief, there was some even in my time, for what boy has there ever been who did not delight in it? And what would the boy be worth if he did not do so? But perhaps I had better say little on this point lest some aspirant for fame should try to surpass his forefathers. Garments nowadays would hardly be improved by having them torn by a seat neatly and secretly prepared for its owner’s reception, with a coating of cobbler’s wax, nor does the countenance or shirt front, even though it be that of a foreigner, look much the better for having had the contents of a bottle of ink over them, the said ink having been quietly deposited in the owner’s hat just before he replaced it on his head, but alas, such have happened even in the King’s School, but tempora mutantur, such things are things of the past, and a good thing too, but I felt bound to hint at mischief to make my account of school life complete.

Well, the school is very different in these days, everything has a new face, but yet the school of our time had charms for our old fashioned selves, which the new ones can never have, but then what is new to us, will in a few years, be old to many who read this, and what changes will you see then. Electricity is only now in its infancy, perhaps then there will be no King’s School required, only a grand central office whence boys at home fondly cherished with maternal care will be instructed through a telephone, a telegraph, or a tele something or other, and that generation will look upon you, my readers, as being just as slow old fogies, as I daresay you consider AN OLD KING’S SCHOLAR

These reminiscences were published in The Cantuarian, in April and July 1886.