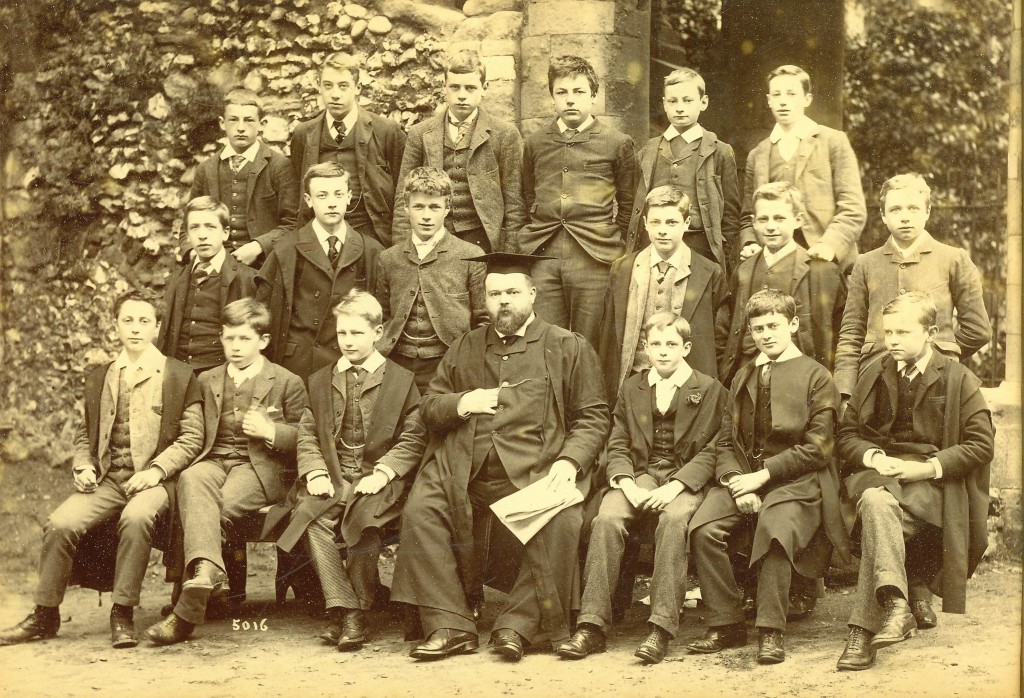

I propose to sketch some of the Masters of old time. It is close on 50 years since I first stepped into K.S.C., so perhaps I may speak without being too presumptuous – though there are others who could speak far better.

I. MR. R. G. GORDON

Tall, straight, but for a slight stoop of the shoulders, grey-clad, alert, out-spoken. Kindly humorous eyes – eyes which pierced us with their direct penetrating gaze – with a smile half-concealed by the longish grey moustache. Clean: he couldn’t brook anything dirty or unkempt. The small boy, on his dismal first day of return, felt himself welcomed and protected by that kindly greeting. A master who felt for the boys – who loved them in spite of their failings – though stern, and perhaps sarcastic, towards the ‘sophisticated’ ones and ready to reduce their self-assurance with humorous thrusts, Such was ‘Cy’.

‘Cy’ – so called, as tradition had it, because in old days as House Master he used to wink over cubicle curtains with one eye – was an old Exonian, from a college which later on I claimed as my own. He came to K.S.C. in January, 1867, and generation after generation passed through his hands, and were all the cleaner and better for it.

Art – in the form of music, singing, drawing, painting, architecture, the beauties of nature, the classics – formed the essence of his soul; and it was the sense of Art that he instilled into those minds which were capable of receiving it. Whether it was some inspired expressions of Euripides or of ‘the Antigone’ – the swallows wheeling madly round the Cathedral towers the autumn colours – the creepers of the Baptistry gardens – or the cadences of music – his soul delighted in them and he trained others to see them and love them too. A school life which consisted merely of lessons and football would have been to him sadly lacking in the building of boys’ characters.

He taught the Fifth – with the climbers of the wisteria drooping over the open, sunlit French windows-in that class-room just beyond the Masters’ Common Room. How glad everyone of us felt when we left the stern severity of Form IV, for the more human and kindly atmosphere of Form V.: and how excellently ‘Cy’ opened our minds to the better influences of Life.

It was the tradition (as now) that out of school-hours the Monitors ran the School – a very useful training for the latter. Masters would tum up on the rugger and cricket grounds, and one, especially, would train fellows for the sports: but beyond this there was little interest evinced in the boys out of school, except by Mr. Gordon and one other who trod in his footsteps.

On off days Mr. Gordon would collect parties of youngsters – lads to whom he felt drawn – and take them to hunt for orchids on Wye Downs or for countryside tramps through Bekesbourne, Eythorne, Minster, etc. He taught us the principals of Gothic architecture and would take us round the Cathedral. He loved the Cathedral and all its old associations and beauties.

The Choral Society, which met on Saturday nights in winter, was a special joy of his. I remember well those cheery evenings in IIIB. – what is now the South end of the Parry. The Choir Suppers and the Choral Suppers and their speeches would send us all home happy and a bit pleased with ourselves.

His own paintings were lovely works of skill – mainly scenes from Norway and Scotland with mountains, mists and rocks in tumbling streams. In ’91 he took me to his wife’s home at Rothie Norman and over the wilds of Sutherland – a grand outing for me with so kindly a host. Alas! one regrets that one was not sufficiently grown out of the caterpillar stage to appreciate all that he was doing for us – and the many disappointments we must have caused him.

After his marriage in 1886, he and Mrs Gordon lived in Hodgson’s Hall. Mrs. Gordon was a replica of himself in the affection she for boys brought within her ken. They had some of us seniors over every Sunday afternoon after dinner in Hall and made us feel at a second home.

To sum up Mr. Gordon, he taught us adolescents to appreciate the humanities of life – beauty, goodness and truth. He was a Master whom every boy at K.S.C. grew to trust and to love.

A senior O.K.S. has criticised my origin of ‘Cy’. The name, it appears, should be spelt ‘Si’, and the connotation was more human and less respectful than that which the term ‘Cyclops’ would warrant.

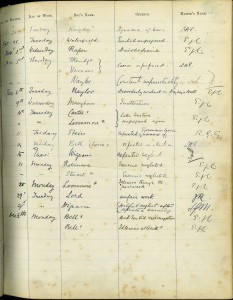

II. THE REV. L. G. H. MASON (ALIAS ‘TAR’)

Fifty years ago I entered K.S.C., a kid of 12: and was duly planted in the Lower Third. My big brother was in the Fourth, ‘Tar’s’ form. From my brother in those days of trepid anxiety before one joined up, I had learnt a good deal of ‘Tar’. In most schools there is a form which is regarded as a purgatory through which boys have at some time in their history to pass, and a master who is a Rhadamanthus. Such was the Fourth, and such was its master: hence I was relieved to find that I was still a long way off coming under Tar’s magisterial discipline.

‘Tar’ was short, extremely stout (rivalling old Bass of the Beverley in circumference) with a stony-white, broad face set off by a short, black, pointed beard. His hair was black and his eyes were very dark, too dark to indicate any real depth of charity. ‘Tar’ drew the line strictly between Out-of-School and In-School hours. Out of School be had cheery or jokey word or back-pattings for any lads he knew well; but in School, he was rather a terror, anyhow to the less dominant personalities among us. Big, strong chaps like A.L. [Latter], P.G.P. [Peacocke] and W.R.M. [Mowll] did not mind him half so much. I think ‘Tar’ was more polite to them.

Often urbane, often wrathful. You could never tell what he would be – or would become – during the five hours of labour.

“Well had the boding tremblers learned to trace, The day’s disaster in his morning face.”

Even big fellows got their elbows hammered down on the desks by their neighbours, or might have to stand with arms raised till exhausted, if they showed neglect or obstinacy. One rather depressed individual came in daily from Margate. I recall ‘Tar’ hurling wrath at him for his translation (Ut capitis minor – in order that less of a head, of course). “Less of a head,” he thundered. “You’ve got less of a head. Why your head (it happened to be unkempt) is just like a BAD BIRD’S-NEST,” and the venom in the “Bad” was wicked. Hardly an encouragement.

One enterprising chap brought back after the holidays a copy of Wickham’s ‘Horace’, an excellent book as it had notes and fine renderings at the foot of each page. This book was not produced in form, but one of the extra-special renderings was. ‘Tar’ gazed at the youth. “Yes: very good; and where, pray, did you get that rendering from?” “From a book, Sir.” “Which book?” H.W.S. stammered that it was written by a man called Wickham. (Now ‘Tar’ relied on Wickham for all his mellifluous and unctuous fair copy translations.) “Bring me that book this evening.” he said. “It is not good for lads not to use their own brains but other people’s. You can have it back at the end of term.”

I still have a grudge against ‘Tar’, in fact two, though he was kindly enough to me. I knew that I was a dud specimen, but being a smug I managed to keep top all the time I was in the Fourth. I was also in ‘Tar’s’ Math. Division, Div. III. On the first day of Maths., after listening to an eloquent harangue on the sins of idleness, untidiness and finger-nails, and so on, we got down to the list of books which we must get. When it came to Euclid, everyone else was told to get a decent book, edited by (was it?) Hall; but, and this in a loud voice for all to hear and perpend, as I was untidy in my written work, I must get Pott’s Euclid.

In time Pott’s rolled up, a horrible black-cloth book with small print, small figures, and, worst of all, only one picture; so that if (as usually happened) the Prop. went on over to the next page, you had to keep on turning back every minute to see where the something angle PQX or QXP was. Now, I ask you all, as impartial and worthy judges, how was that calculated to improve my lack of neatness? It meant double the labour for me to learn one prop. while all the other fellows, smugs or loafers, had a picture printed on every page, and nice big ones too. It rankled then; it rankles still.

Again, at Easter I was top in Div. III. Maths., and expected promotion, and with it, joy, for dear old Gordon took Div. II. No, I was made to stay a year in Div. III. It appeared that it would be good for me – reasons not stated. At the end of that year, I was miles up, almost among the wranglers of Div. l. And the only motive I have been able to sec about it all was the desire of ‘Tar’s’ to show to Cy that a shining light under ‘Tar’s’ tuition could beat all the 2nd Div. of Cy’s. Poor I was the sacrifice.

‘Tar’ was keen on cricket and athletics. In spite of physical difficulties he could punch the bowling pretty hard at the nets. He spent hours in coaching R., who became one of the best cricketers that we had. Also in athletics he spent the sports time daily in coaching fellows. In fact be ran our sports, theatricals, and Speeches. Many still recall his bullet-like shout of one syllable “Are you ready off” for the starts. He was extraordinarily good at theatricals, and produced very good results out of very raw, self-conscious material; and the Speeches (we had five then) were always done well. One can see him still, sitting in the Masters’ row, screwing up his face and lips to correspond to the action or words due on the stage; his prompting was always there ready for us. (How many of us are left who remember Atherton’s “revenons a nos moutons”?)

When old Gordon married and removed to Hodgson’s Hall, ‘Tar’ became Doyen of the Masters’ Common Room. Having an outsize waistcoat, ‘Tar’ felt the need of plentiful food and drink, perhaps more than we skinnier brethren. Anyhow, as before the dinner hour he leant out of that window over the Grange entry, he was full of the milk of human kindness, chaffing fellows as they passed down below: and when the gong went, he sailed down singing to the Common Room, where he was reported to exercise a discipline as stringent as in his class-room.

With all his queerness he represented a type quit common once but now almost obsolete, and followed a tradition of education which, once almost universal, is not approved by modern authority. He certainly ruled as Tennyson’s ‘Captain’ ruled. And if it be the idea of education that a boy should “Fit his task”, know his books, fail in no point of translation or in any historical or mythological allusion, he was an extraordinarily good teacher. His boys at least knew their Horace.

An O.K.S. himself, he was a master for some forty years; and when his time came to retire, he suffered much from rheumatism. He lingered on in Canterbury, knowing no other ‘home’ for many years, with few friends, until a kindly Death beckoned to him.

III. MR. E. J. CAMPBELL

I recall a conversation I had with my elder brother (L.W.) in 1884. He had been at K.S.C. for a year, and had just risen to the Fourth. During that uneasy period before my actual joining, when a Public School loomed dim and rather terrifying in front of me, L.W.S. was surmising into which Form I was likely to be placed. He said “I expect it will be under old Scragg.” “What kind of master is he?” I asked. “He scraggs fellows,” was the reply. “How does he scragg them?” I asked in trepidation. “He takes them by the neck and shakes them violently.” So at night I prayed that I might not be put under ‘Old Scragg’. And to my joy I was put into the Lower Third, under old Ritchie; and I had a whole term before I came under E.J.C.

Now there was nothing at all terrifying about old Campbell (alias Kimble) out of School. He always seemed genial and cheery. He·was somewhat inclined to stoutishness, of normal height, reddish moustache, hair rather thin above, and he wore spectacles and chalk-stained clerical garb. But what was a peculiarity was his daily change of temper during School hours. If he began the day’s work full of easy jokes and smiles, as sure as night follows day, he would be in a pretty bad temper before noon. And vice versa, as surely as day follows night.

He was then (1884) senior Maths. Master, having, I think, succeeded Hodgson as such. Hodgson had taken over The Parrots. The incipient Army Class had begun with some extra Maths. for candidates. My old friend Alec Bredin was one of the earliest, with Welstead and another; and they had to be pushed on in Maths. more quickly than we humbler fry. But (forgive me, Bredin) they had a ghastly job of it with Euclid ; and old E. J .C. (to the hidden delight of us others who were poring over our own ‘examples’) began to whisk his gownsleeves about, and rave through hissing teeth, and would take (let us say) Welstead and rub out the figure on the board with his nose.

And this was mild compared with his outbreaks against one or two unfortunates of the Mid Third who could not give him the future of ερχομαι; nor even translate ‘Balbus aedificabat murum’ successfully. I recall a long and very happy fellow who out of School was full of life and jokes; but was a hopeless duffer in Latin and Greek. E.J.C. had a bad ‘down’ on him, and he got it ‘in the neck’ metaphorically and literally nearly every day, sometimes getting considerably bruised.

Before coming to Canterbury he had been a Master at Westward Ho I under that remarkable man Connell Price to whose credit may be counted the upbringing of Rudyard Kipling and ‘Stalky & Co.. He is not immortalized in that historic volume, but ‘Stalky’ (General Dunsterville) describes him as a ‘very peppery individual who endeavours to rule by fear which does not pay in the long run with boys.’

You must remember that these days were not so far separated from the pre-Arnold times as are the present ones. None of us thought of protesting. We took it ns a matter of course. And still less did we want to protest, for within a short time E.J.C. was all happiness and smiles again; and as I have said, he was always jolly out of School.

I recall one day when he had come in to School full of happiness and jokes. We were all seated in a three-sided rectangle in front of him. E.J.C. made a good joke and we all duly laughed; but Rumford (yes, he that singeth) went on laughing loud und inordinately for some time longer. E.J.C. got offended and suddenly changed from joy to wrath, and Rumford got it badly. He was a good master and brought on his Mathematical ‘lights’ extraordinarily well; and was always kindly to me in spite of my heresies as regards Ratio and Proportion; and I was by no means the only one who felt a considerable affection for him, not untinged with fear.

A chap from Ramsgate had a very bad time with E.J.C. At last he couldn’t stick it; he dodged Saturday afternoon Cath. and took to the road for home. His absence having been noted at call-over and also after Cath., E.J.C. drew a bow at a venture and went off on his tricycle (one large side wheel, and two little ones opposite) to hunt along the Ramsgate road. Next Monday he described the event. He had a heresy about the letter ‘R’’ which he pronounced like a ‘V’.

“I went along on my tvicycle, and in the fields beyond Stuvvy, I caught sight of him cvossing a field. I went up and caught him and bvought him back in tviumph at the wheels of my chaviot.” Of course we all laughed; but all the same all our sympathies were with the Fugitive. Next term he did not return, and life at K.S.C. had not been very kind to him.

As I went on up the School after my term with him in 1885, I came again under him in the Senior School Maths. Division. All those years (’85-’91) E.J.C. was getting more and more beloved. It was seen that he was trying hard to control that violent temper; and he succeeded in time. Our fear had given place to affection.

He was, with other accomplishments, an expert photographer in days long before the Kodak film and there are somewhere beautiful pictures which he took of the Cathedral and its surroundings.

I was with old Gordon in Scotland in the summer of 1891 when Gordon got a wire to say that E.J.C. had died, down at his home in Cornwall.

IV MR. J. RITCHIE

Mr. Ritchie was on the short side of heights, very thick and strong and very cheerful and genial to all. I don’t think any one of us had any grouse against J.R., in fact several of us were inclined to trade on his good nature and be rather talkative in class, till his very severe gaze through his glasses, and his prompt staccato gruff voice bade us be jolly careful, else worse would follow.

He had sandy hair and short whiskers, with a cheery and florid face, and was in charge of the Lower Third. That was my first form after entry, and J.R.’s kindness to me was perhaps as good an introduction to Public School life as a kid needed. Shortly after my first term, he was allowed the right to cane fellows in form, and this no doubt had its required effect on too exuberant spirits. But I doubt whether his infliction of the rod was as severe as the crimes demanded. Our impression was that a hefty bruiser, made up of dense muscles, couldn’t hit nearly so hard, or so painfully, as a lither one. Anatomists may perhaps agree. Anyhow, I remember watching the face of one Douglas at the “Bendover there”; during the infliction of stripes he was grinning at us all, and I believe he had no copybooks concealed.

J.R. held his lessons in the School Room, at the far end. The respected Lower Sixth went into the Rabbit Hutch, to be polished up by L.H.E. (whose turn in these notes will come before long). J.R.’s rooms were, for most of my time, at the far end (easterly) of the top Grange passage. He was of a musical turn, and kept a very good harmonium; and it was quite nice on summer evenings to hear the music of this floating forth from the jasmined walls of the Grange. An air seemed constantly in his mind, for he would generally pass you with the low pom-pom-pom of some tune. He and old Gordon were our basso-profundos of the choir and of the Choral Society. He would often let me come to his rooms and play on his organ.

He and Mr. Hodgson and Mr. Field were the founders of our Boating Club. I believe Mr. Field and he had both been in the same Corpus boat at Oxford, where he was accompanied on the towpath by a Dalmatian dog which, I think, followed him to Canterbury.

Altogether everyone liked J.R., and his amusing speech at one choir supper when he spoke up for the duffers still lingers in my mind, along with his regular song ‘The Heathen Chinee’. He was always ready to joke, and amid the solemn arc of masters at week’s places, he was the only one that looked genial, except when he surreptitiously passed round his lightning sketch of some poor wight which brought grins to the mouths of all that serious throng. He was a very good artist, and taught drawing in the Lower School. He and Gordon were by nature and artistic predilections very good friends.

We learnt our ‘Artifex and Opifex’ pretty well under him, and ‘Incipe placato’s’ were not dealt out too freely.

N.B. Before Dr. Field’s time, impots were confined to so many hundred lines of ‘Incipe placato, Caesar Germanice, vultu’ with its three next lines (now speak up, who of us can get any further?) repeated over and over again. Some cute fellows did rather a good trade in those they had “forgotten to show up” and which the master concerned had forgotten to demand. Then on an ill-starred day, Dr. (then Mr.) Field came along and started the horrible idea of making the criminal copy out some page of history or Shakespeare – which did not seem to be the game. He had a vile Invention called the Date Card containing a list of dates and “silly snippets” of indigestible information. Who wants to know the time of day at Aden, or its distance from London? Still, some of us from frequent transcription did know it.

V. THE REV. L. H. EVANS

When I came as a kid, L.H.E. came as a Master. That was in September, 1884. From his wind-swept home of Scremerston on the cold Northumbrian coast – from his school, Durham – from Cambridge (Pem. was it?) – with the wreath of Proxime Porson adorning his brow (the winner must have been Lambus himself– re-incarnate), he came South to K.S.C. He brought with him a long serious face, black eyebrows and moustache, a Scotch terrier hight Tiddle-de-Winks (‘Winks’ for short, a title quickly – by induction – transferred to his master) and a lean muscular activity. Thus came he to the lime-tree shades of the Cathedral – and he has been part and parcel of the School ever since. I forget in what year he resigned his mastership and took to parochial work, but I know that his affection for the old place, and the old boys, is as strong as ever. For many summers, after his retirement, he has turned up to be the adjudicator of Junior and Senior schools.

He began with the demi-gods of the Lower VI., in the Rabbit Hutch: but on the departure of C. H. Douton for the Isle of Wight College in 1885, he took over as his substantive post the charge of the Upper III. To us youngsters he was a grim (because unknown) terror, over those iniquitous paradigms. In those early days, he never laughed in Form, and little out of it. He was to us a dim, fuliginous man. But not one of our more daring hecklers or tryers-on ever scored off him. Such folk were promptly put into their proper place by some quiet, yet effective, reply.

Thus he allowed no nonsense: and his slow drawly voice became a fruitful source of plagiarism in the Dorms. He earned our respect on the Beverley, though he laid no claim to Blue-ship. Also he turned up regularly at Rugger matches – with Ritchie and Winks. In those days such show of patriotism did not form part of the magisterial Code of Honour. ‘Wink’s’ presence was duly noted and appreciated. It was even reported that soon after a Headmaster came, ignorant, of course of the ways of boys, he asked someone of a group, “Who told you that?” “Mr. Winks, Sir.”

He remained a respected enigma to all of us adolescents till we emerged into the butterfly stage of the Sixth. Then we came to know the real L.H.E. – kindly, affectionate (though quite undemonstrative), helpful and brilliantly clever. What Gordon did to our crude ideas of Art, that L.H.E. did to our reckless ideas of literature. Many an evening, in his rooms by the Gym, we met to read Talfourd’s Tragedies, Browning and Co. Countless eves he had Parker, l.ongfield, Moule, myself and all of us in, to go through our Elegiacs or Iambics, showing us how to turn into the neatest Greek or Latin the spirit, instead of the words, of the poem in question: and ruthlessly exterminating our somewhat uncalled for πεν γαρ-s and γε-s and όυν-s. I can even now see the extremely handsome red-ink lettering of his Greek emendations.

By nature, L.H.E. and Gordon were close friends; and though it has been the tradition of K.S.C. that out-of-school hours, it is the monitors who bear the responsibility for good order and discipline, it is a great thing to find among the masters those who give up their time and energies to improving and inspiring the minds of both monitors and οι πολλοι in general. And in my time it was these two great souls – Gordon and Evans – who not only laid themselves out to help us all upwards, but took a delight in doing so.

P.S. I must close these notes now, for these five great men of the past, ‘Cy’ (?), ‘Tar’, ‘Kimble’, Ritchie and ‘Winks’ formed the permanent staff of my day. Others came for a spell and passed on to other spheres: and among these, Hallam should be recorded.

The Modern Languages side was somewhat unfortunate, though it did provide us with the lighter vein of comedy to relieve the grim seriousness of the classics. Outstanding in this department was the strong, jolly, forceful personality of Hallam, who, sad to relate, went off early to start his own Army Candidate School at Dresden. That was a bad loss to K.S.C. Of course, much might be said of Dr. Blore, Dr. Field and Mr. Hodgson: but I have not the cheek to criticise such mighty ones. My own verdict would be considerably biased by either reverence or affection. Besides, whereas we ordinary chaps can realize that, as a Genius, a ‘Master’ is only a big school boy like ourselves, a Headmaster is a being on a pedestal far above the level of our eyes.

To me (and I hope to others) these notes have brought back the vision of the erect Gordon – handsome face, military moustache, brushed-back hair, Oxford M.A. hood, pounding away at the bass of the Anthem and sharing old Loosemore’s copy; of Tar’s portly, blackbearded form sailing nautically across the Mint-Yard; of Kimble fidgeting nervously with the front edge of his surplice as he hurried through the words of a printed (?) sermon in chapel; of Ritchie playing a tune on his teeth with his finger nail; and of the long lean face of L.H.E., hiding beneath that mysterious exterior the warmth of so kindly a soul. Valete.

John Hubert Smith was at King’s from 1884 to 1891. He was in the 1st XI and 1st XV and Captain of School. After Exeter College, Oxford, he worked mainly in Kutch, India. These reminiscences were published in The Cantuarian in 1933-35.