World War I

In the summer of 1914 I was living, with my family at Canterbury, having just completed my first year at the (senior) King’s School. Like everyone, else I had joined the School Officers’ Training Corps, and at the end of the summer term had gone off with the school’s O.T.C. contingent to the annual Public Schools’ camp on Salisbury Plain and was there when war broke out on 4th August. I remember wild rumours flying about the camp about (imaginary) naval actions in the North Sea. The regular officers running the camp having more urgent things to do, the camp soon broke up. The journey home was much interrupted by passing troop trains.

I arrived back during the annual Canterbury Cricket Week, a great event in my life. At the age of 14 I was as much interested in this as in the war, if not more so. I remember buying 5 small national flags with metal staffs, those of the original Allies – England, France, Russia, Japan and Serbia – which I affixed to the handle-bars of my bicycle. For this excess of patriotic zeal I was ticked off by my elder brother Bill, as beneath the dignity of the VIth form to which I had just been promoted.

In September I went back to school and the remainder of my time there until I left to join the forces in May 1918, was spent against the sombre background of the War. Numbers fell considerably, for though there was no invasion threat there were periodic German air-raids over London and the Home Counties, first by Zeppelin airships and later by Gotha and other aeroplanes. E. Kent was a relatively exposed area and some schools moved to the West Country or elsewhere. In fact no air-raids affected Canterbury during this war.

Large numbers of the preceding generation volunteered at once, as did each succeeding generation of school-leavers, also later on a few of my own contemporaries, such as Trevor Champion and Norman Murgatroyd, both of whom enlisted n the ranks and were wounded. There was no conscription until much later in the war, the minimum age for enlistment was 18. Champion and Mutgatroyd had understated their age.

Casualty rates were terribly high and an increasing number of my near-contemporaries were killed or wounded. Later on, when I became an editor of the school magazine, I had the sad task of writing obituaries for boys (and masters) many of whom I had known. More than once the O.T.C. provided firing parties at their funerals.

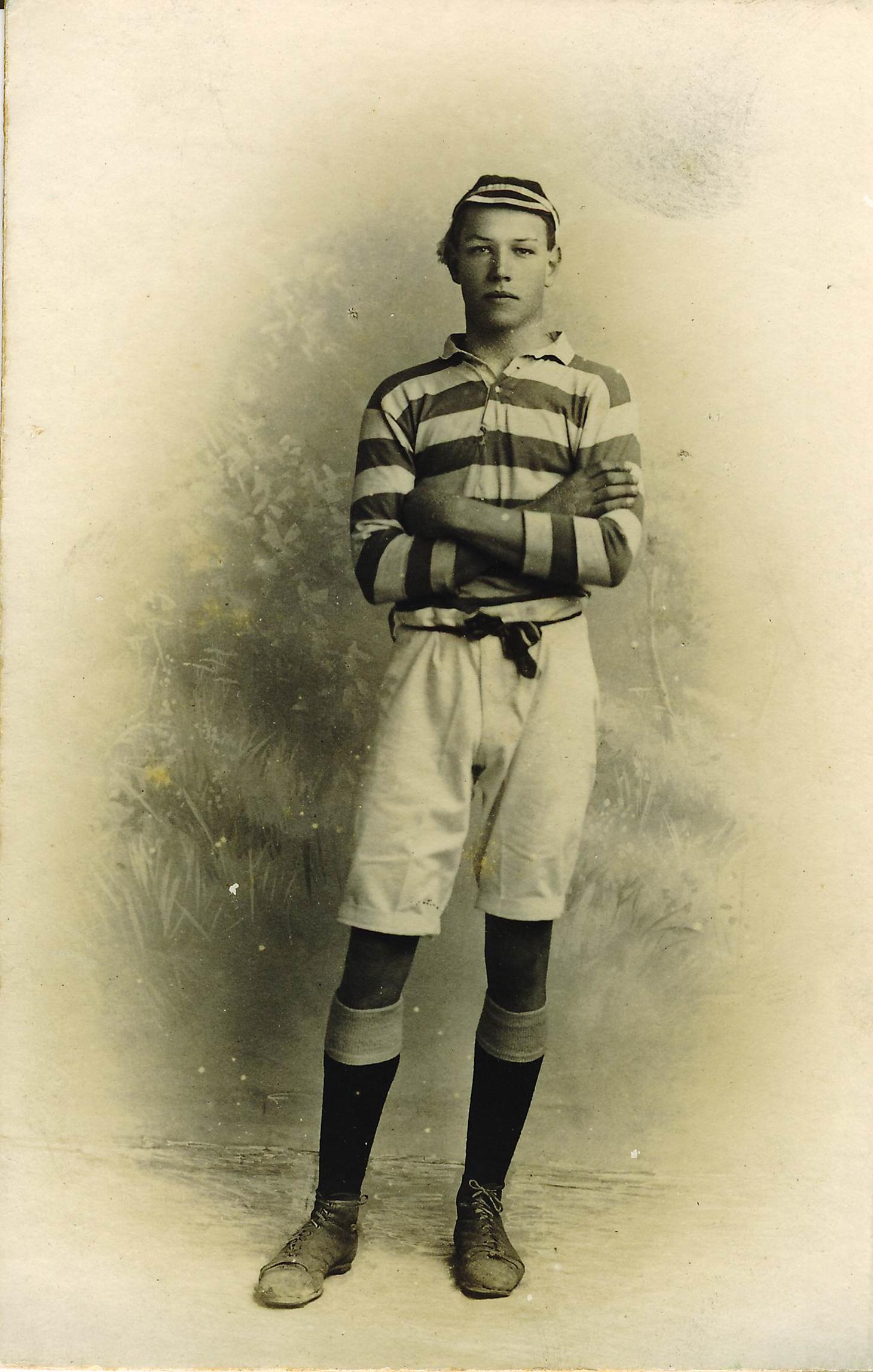

Very soon there there no young masters left at school,·their places being taken by elderly or retired men, with a few precluded by ill-health from enlisting. Inevitably standards, both academic and athletic, fell, with this somewhat motley staff and decreasing numbers of boys. Winning prizes and “colours” became less competitive and prestigious. I gained a number of both and was Head of the School and Captain of the cricket XI, but I often wonder how I should have fared but for the War. Prizes degenerated from handsomely bound volumes with the school crest to War Savings Certificates, long since gone with the wind.

O.T.C. training took up much of the time outside school hours and it was taken for granted that one would join the forces on leaving. The average survival of a junior·officer in France was said to be 2 to 3 weeks before he was killed or wounded, but so adaptable is the normal boy that this prospect was accepted a fact of life, and made no special impression on me at the time; but I do remember at the end of the war feeling as though black curtain had been rent apart, giving a view of the future other than the army and life – or death – in the trenches.

In the holidays one did “war work”, for which there was no lack of opportunity. Pay, in terms of those days was very good and one could earn £3, £4 or even £5 weekly, wealth for a school-boy. There was farm work of various kinds, harvesting, fruit-picking, sawing up pit-props (for trench revetment) etc. One job I had was “hop-stringing”, two boys working together, one on high stilts attaching strings to the top wires, the other on foot tying-in these to the two lower wires.

I was a day-boy at school until the Easter term of 1917, when on being appointed successor to the Head of the school I became a boarder in the School-House. I took over the following term. Food for boarders, never luxurious, deteriorated during the War with the general shortage caused by the German submarine campaign. Our basic fare was “taws”, as we called the thick slices of bread and margarine which were the basis of our breakfast and tea. We had a solid lunch but nothing after tea except what we provided for ourselves. There was a good tuck-shop, where a large roll and butter and cup of tea cost three-pence. Later on an unpalatable maize bread was substituted for wheat bread. This led to mutinous rumblings and as Head of the school I was told by the headmaster (“Algy” Latter) in no uncertain terms that I must put a stop to this by explaining the national emergency.

In 1916 my elder brother Bill left school to join the Indian Army via the cadet college at Quetta, and the following; year my·own turn came. At the end of 1917 at the age of 18 I registered for service, though not “called up” until the following May. I was then posted to the 15th Officer Cadet Battalion, stationed at Romford in Essex. O.C.B.s were the equivalent of the second war O.C.T.U.s, though unlike the latter, previous service in the ranks was not essential. By this time the barrel was being well and truly scraped for officer material. One of the 4 companies of our battalion consisted of tough ANZACS (Australian and N.Z. N.C.O.s), the other 3 of British N.C.O.s (some of them regulars with pre-war service) with a few school-boys like myself. At the time I was young and uncritical but I later realised what poor material many of us made.

O.C.B. courses, originally lasting 3 months, were progressively extended and by 1918 the period was 6 months. I enjoyed my training. I had been company sergeant-major in the school O.T.C., and drill and tactics were no problem; and other subjects such as map reading, military law etc. were easy to assimilate. Not so however for some of the old army “sweats” who found the minimal maths involved in map-reading all but beyond them. So the school-boys would coach the elders in this, and the old soldiers taught the school-boys how to clean their equipment and generally the run of barrack life. For that is what it was; we were billeted in a large dilapidated country mansion, Gidea Hall (long since pulled down) and slept a dozen or so to a room on camp beds with army blankets. It was a fine summer and well I remember the route marches, tactical and map-reading exercises in the Essex countryside.

Food, though better than at school, was very moderate in quality and sometimes short in quantity, but there was a good canteen to supplement this. As a private soldier I received army pay of 1/6 (7½p) daily. At the outbreak of War it was 1/-. But this went unbelievably far in those days.

We wore rankers’ khaki uniform (tunic, trousers and puttees) until about half way through the course a number of London military tailors arrived to· measure us for officers’ uniform – “glad rags” so-called, which we wore thereafter on leave or for special occasions, with white cap bands and Sam Browne belts (without shoulder-strap) and of course no rank insignia.

By mid-summer 1918 the tide of war was finally beginning to turn in favour of· the Allies and·it·was becoming increasingly clear that we should not be needed. Passing-out exams were held in November and the same month came the Armistice. With general demobilisation in prospect there was no question of our being appointed to a regiment, except that at one time there was talk of our being; commissioned and sent to relieve officers in the British forces at Archangel supporting the “White” Russian anti-Soviet armies. This came to nothing.

For some time the War Office clearly did not know what to do with us. In the end it was proposed to continue military training but to subordinate this to more academic instruction. This nearly caused a mutiny. Ex-N.C.O. cadets, some of them barely literate, feared that they would ipso facto be discriminated against.

Ultimately in January 1919 we were simultaneously gazetted second lieutenants and demobilised, in time for me to go up to Oxford for the Hilary term, having lost through the war only my last term at school and the autumn term at the University.

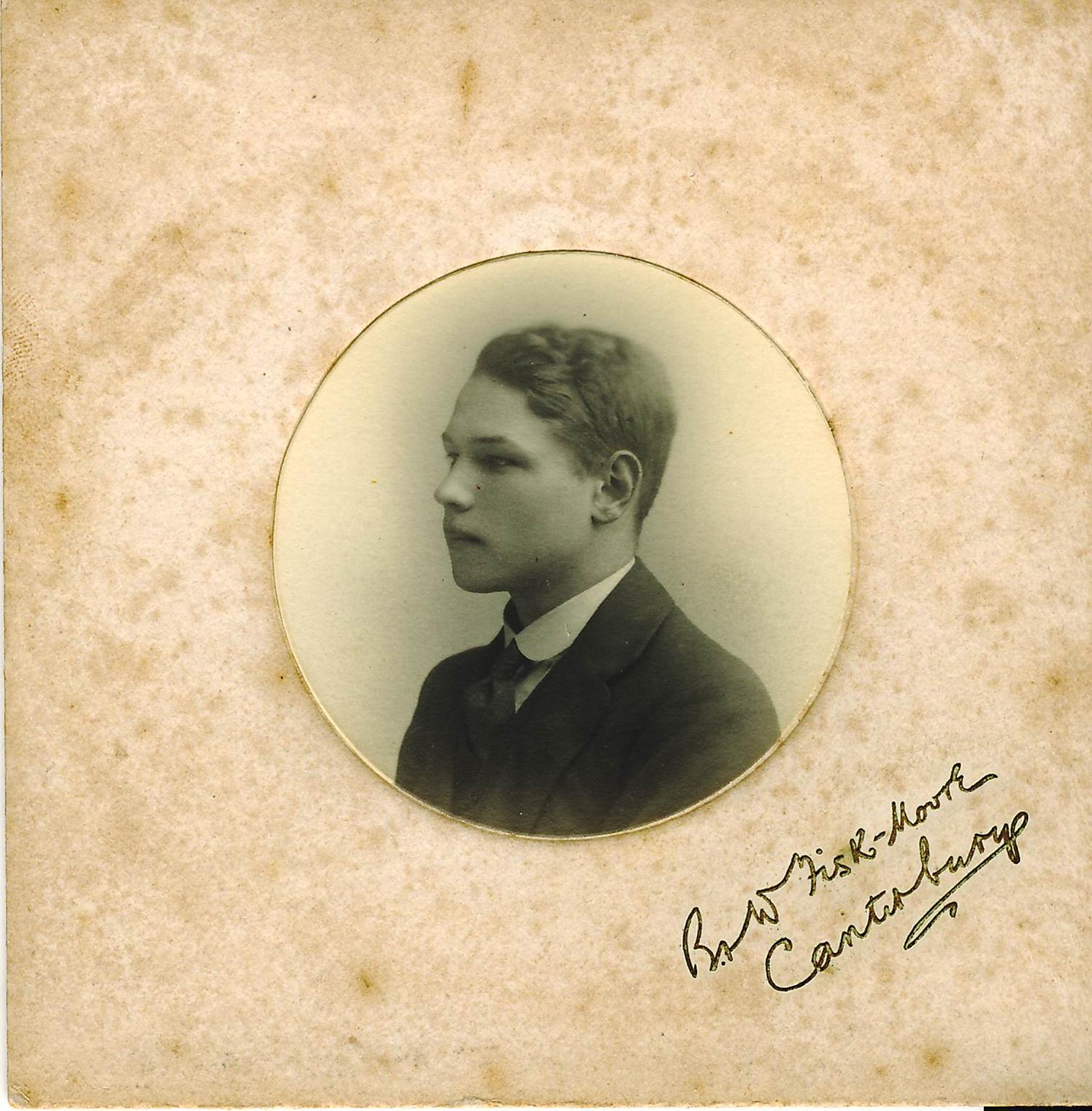

Arthur Dean joined the Junior School in 1909. He was at the Senior School from 1913, was Captain of School and Captain of Cricket. He went to Trinity College, Oxford and from 1922 worked for John Swire & Sons, mainly based in China. During the Second World War he was imprisoned by the Japanese. From 1947 until he retired he worked in London. His ‘Recollections of Two World Wars’ were written for his family in 1982.